The promises or hype of educational technology are an unfortunate central part of our long-standing tradition of attempting to use technology to change education. Will the hype around Artificial Intelligence (AI) be any different than the hype that we have experienced this past century? Should teachers be fearful of being replaced by AI? The answer depends on the type of the teacher. Before, we address who should be wary of AI it is important to set the context.

Schools have had a longstanding immunity against the introduction of new technologies. In 1922 Thomas Edison predicted that movies would replace textbooks. In 1945 one forecaster imagined radios as common as blackboards in classrooms. In the 1960s, B.F. Skinner predicted that teaching machines and programmed instruction would double the amount of information students could learn in a given time. Filmstrips and other audiovisual aids were fads thirty years ago, and the television, now seen as a supplier of brain candy, once had a sterling reputation as an education machine (Seidensticker, 2006, p. 103).

We have seen over a century of predictions and subsequent failures about how technology would radically change education as we know it and yet we still continue to buy into these notions. In The History of Teaching Machines, Audry Waters (2018) shares the progression of our infatuation with the automation teaching. The difference with the 21st century and the digital information age is that we are moving through these hype cycles at a significantly faster pace.

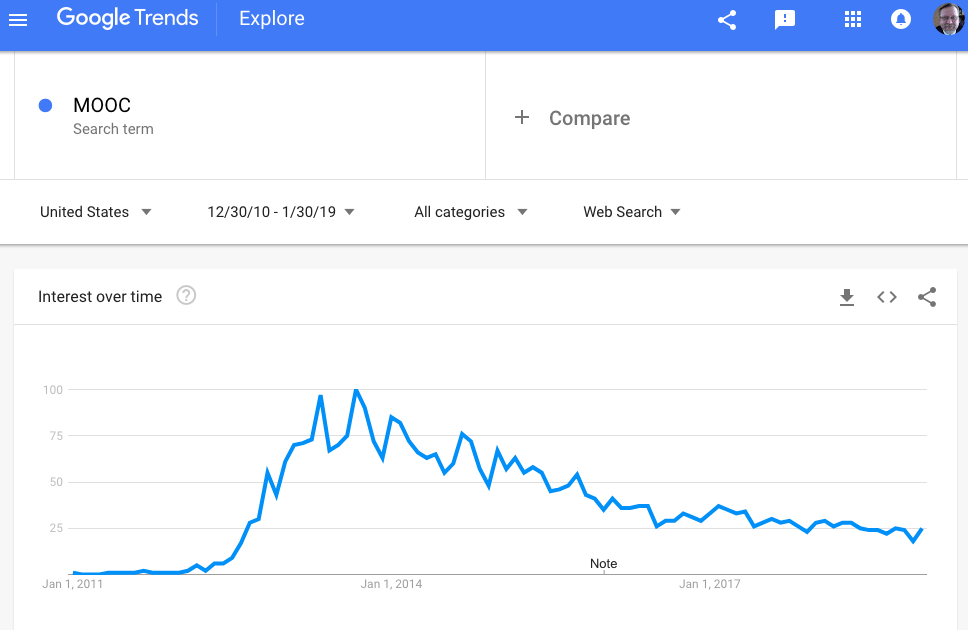

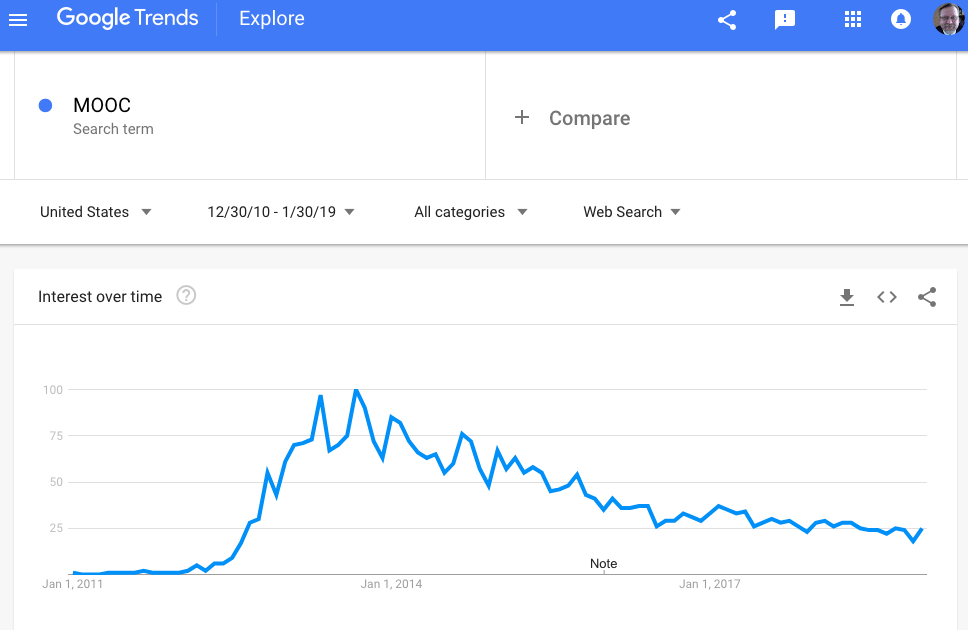

Just consider the hype around MOOCs that exploded in 2012, peeked in 2103, by 2014 many were reporting the problems with MOOCs (Friedman, 2014), and were declared complete failures by 2017 (Shahzad, 2017). I have been on the cutting edge of educational technology use and started teaching completely online in 1995 but knew from several decades of experience of using technology to enhance learning that the MOOCs would fail because of its emphasis on the information delivery and regurgitation model of instruction and that MOOCs ignore the fundamental presupposition that teaching and learning is uniquely human relational activity.

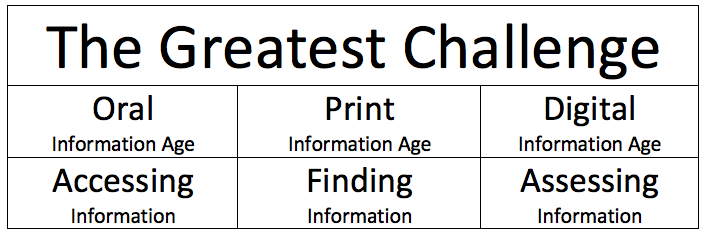

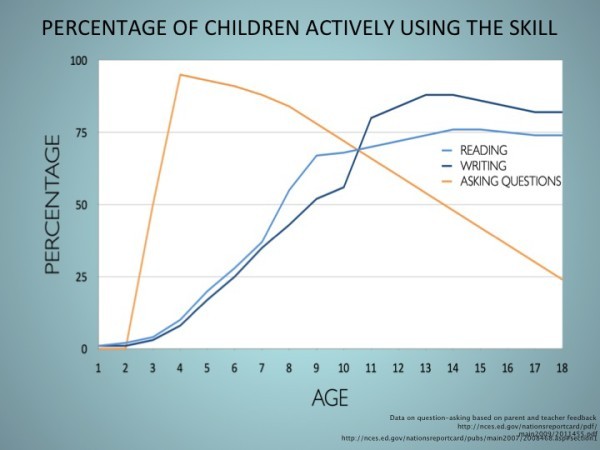

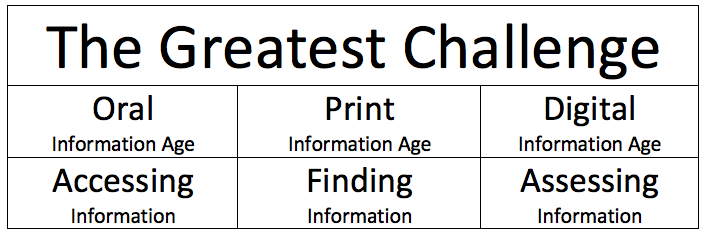

Another reason we fail in recognizing and using the potential of educational technology is that we ignore the challenges of our current information age. My colleagues Bill Rankin and George Saltsman (2010) offered the following summary of the challenges of the information age and how we as teachers should respond to the challenge of the digital information age:

Even though our educational system is still mired in the print information age, if we assume that we are currently in the digital information age then consider the following:

Even though our educational system is still mired in the print information age, if we assume that we are currently in the digital information age then consider the following:

If I imagine my primary job as a teacher is to serve information, am I helping solve the current informational problem or make it worse?

And given the vast complexity of the informational network, if I insist on my centrality, does that establish or harm my credibility as a teacher?

If assessing information – and the wisdom & experience that requires – is the central challenge of the current informational age, are teachers more or less necessary?

Considering the overwhelming amount of information that that average 21st-century learner has at their disposal there is no denying that assessing information is one of our biggest challenges and subsequently teachers are more important than ever.

This brings me back to the initial question – Should teachers be fearful of being replaced by AI?

If you are a teacher that is currently operating in the 19th and 20th-century information transfer model of education focused on delivering content and then checking that delivery through a standardized testing model established in 1914, then you should be afraid of AI. Any standardized rules-based system can be automated. With the advances in AI that we have seen in the past several decades, we are only a short time away from the development of algorithms that can automate this information transfer model and eliminate the need for teachers who are using this information transfer model.

OR

If you are a teacher who believes that learning is the making of meaningful connections and your role is to create a significant learning environment in which you give our learners choice, ownership, and voice through authentic learning opportunities to help them make those meaningful connections than you will have no fear of being replaced. You are preparing your learners for a life filled with innovation and exploration.

Is your teaching future in jeopardy?

A more important question may be: Are you jeopardizing your students future by conditioning or preparing them to be replaced by a more efficient and automated information regurgitation algorithm?

References

Friedman, D. (2014) The MOOC revolution that wasn’t. Techcruch. Retrieved from https://techcrunch.com/2014/09/11/the-mooc-revolution-that-wasnt/

Rankin, W., & Saltsman, G. (February 2010). Teaching and learning in a mobile world: Engaging a new informational model. Presentation for the Teaching and Learning Initiative Conference. Houston, Texas.

Seidensticker, B. (2006). Future hype: The myths of technology change. San Fransico. CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers

Shahzad, S. (2017) The traditional MOOCs model has failed. What next? Educational Technology. Retrieved from https://edtechnology.co.uk/Article/the-traditional-moocs-model-has-failed-what-next

Watters, A. (2018). The history of teaching machines. A Hack Education Project. Retrieved from http://teachingmachin.es/timeline.html